Albanian society has sunk into such a profound crisis that many people now resort to extreme global comparisons. The political exhaustion in the country is so deep that some express their hope for change through dramatic parallels. In recent days, statements have circulated that echo international events, claiming that Edi Rama would be “the next after Maduro.”

A video posted on Sali Berisha’s official Instagram page shows demonstrators shouting: “Hajdut, hajdut, jep dorëheqjen! Lëri shqiptarët të hanë bukë, mor qen!” (in English: “Thief, thief, resign! Let Albanians eat bread too, you dog!”).

In doing so, they are acting in line with what Abraham Lincoln described as a democratic principle in his 1861 inaugural address: when a people grow weary of their constitutional right to change their government, they should exercise their constitutional right to resist, dissolve, and overthrow that very government.

Source: Official Instagram page of Sali Berisha

But what exactly has driven a population to such a state of fatigue?

While the world debates geopolitical conflicts, wars, and diplomatic power plays, a different crisis is unfolding in Albania—one that receives almost no international attention yet threatens the daily lives of millions. The country is drowning in waste, breathing toxic air, and living with infrastructure that has collapsed under the weight of time. The consequences are visible, measurable, and devastating—the product of political choices that have consistently prioritized spectacle over substance.

Albania ranks among the world’s lowest greenhouse‑gas emitters—not because of sustainability, but because of its small size and limited industrial base. Yet despite this small global footprint, the country suffers intensely from environmental degradation of its own making. Millions of cars clog Tirana’s streets because there is no metro, no suburban rail, and no modern public transit of any kind. Plastic waste accumulates in rivers and fields. Floods devastate entire neighborhoods because the sewage system has been neglected for decades, as Albanian radio stations reported even today. The result is a toxic mix of smog, waste, and collapsing infrastructure that shapes daily life far more than any distant geopolitical crisis.

Nowhere is this state failure more visible than in waste management. Plastic dominates daily life: single‑use bottles, cans, packaging, and bags define the urban landscape. Garbage containers overflow, releasing a heavy stench even in winter, and a significant portion of the waste ends up in the sea. This is not a cultural trait—it is the direct result of political decisions that prioritize short‑term visibility over long‑term public health. High‑rise towers appear overnight, yet the basic infrastructure remains stuck in the 1990s.

The health consequences are no longer abstract. When medicines fail to work because—as many citizens believe—expiration dates are altered or drugs are improperly stored, distrust in a system that already makes people sick grows deeper. In a country where air, water, and food are already compromised, uncertainty about the safety and reliability of medication becomes an additional threat. The frustration with a system that neither protects nor reliably heals is correspondingly high.

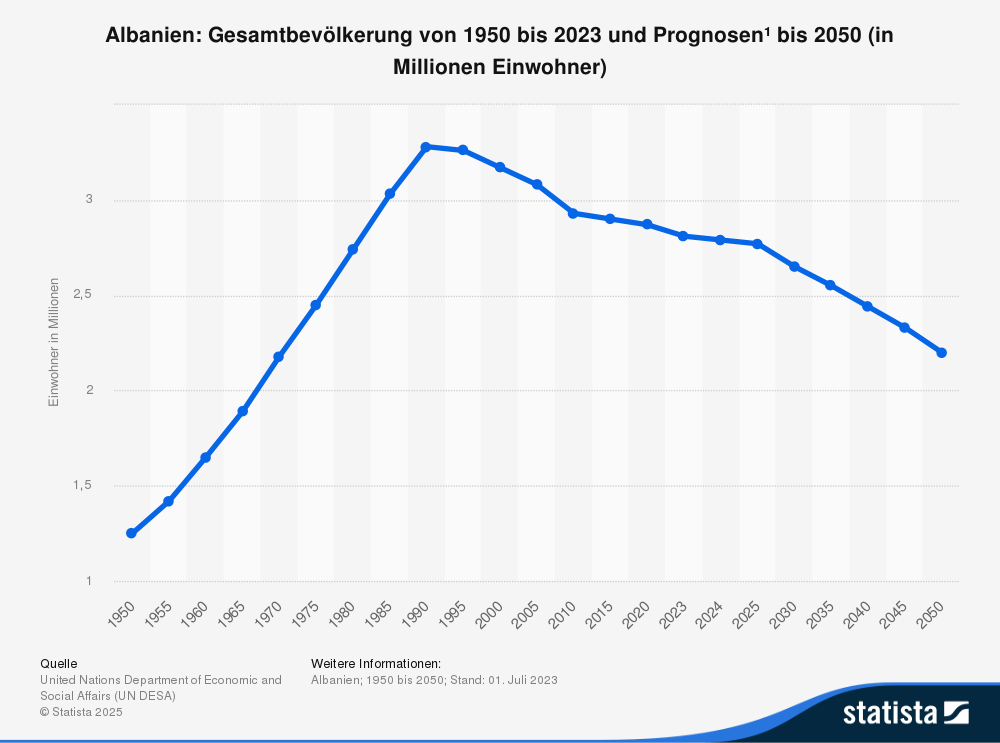

Demographic projections reinforce the scale of the crisis. Major international statistical institutions—including Eurostat, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), and Germany’s Federal Statistical Office (Destatis)—all forecast a significant decline in Albania’s population over the coming decades. The trend is driven by two converging forces: sustained emigration and a steady rise in mortality as the population ages and chronic health conditions increase. In a country already struggling with pollution, inadequate healthcare, and deteriorating infrastructure, the combination of higher death rates and mass outward migration accelerates a demographic contraction that European demographers now describe as structural. Albania is not only losing its young people—it is losing its future population base.

The international perception of Albania is distorted. In Brussels, the country is praised as a reform success because a handful of politicians have been convicted of corruption—a requirement that mattered for EU accession. Yet while anti‑corruption efforts are celebrated, other fundamental conditions remain untouched: clean air, functioning waste management, and a justice system that protects rather than endangers its citizens. The daily lives of Albanians do not improve simply because three or four officials are in prison, especially when corruption persists in everyday institutions—most visibly in the judiciary, as the recent murder of a judge painfully illustrates. What is presented as progress is often only a façade: artificially inflated towers built through money laundering, and roads financed with funds confiscated from organized crime. Behind this polished surface remains a state that neither safeguards its people nor offers them a reliable future. Is this not precisely the kind of political exhaustion Lincoln described—the moment when a people grow tired of expecting change through constitutional means?