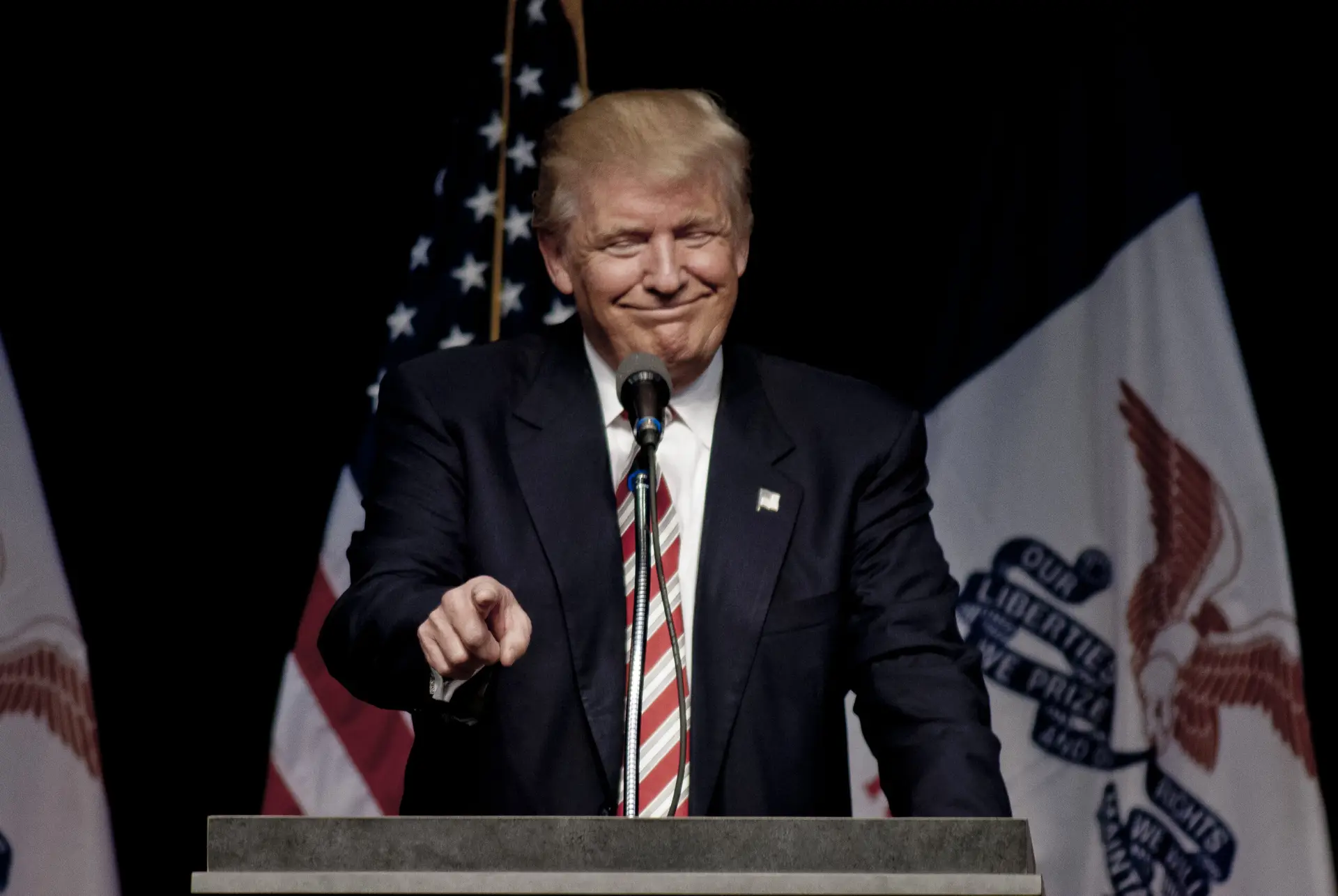

In a recent CNN interview, former national security adviser John Bolton remarked that Donald Trump “may strike Iran,” adding that “no decision is final.” At first glance, this sounds like the familiar ambiguity of American foreign policy messaging—a way to keep options open, to avoid committing to a single course of action, and to maintain strategic flexibility. But Bolton’s phrasing does something more consequential: it exposes the underlying architecture of U.S.–Iran relations, a structure in which diplomacy and the threat of force are not opposing strategies, but mutually reinforcing instruments designed to maintain Iran in a state of permanent strategic vulnerability.

Why negotiate with a state you are simultaneously preparing to strike?

To understand the logic, one must abandon the conventional assumption that diplomacy is a process aimed at compromise, mutual recognition, or conflict resolution. In the U.S.–Iran context, diplomacy functions as a tool of management, not reconciliation. The purpose of the negotiation is not to reach a stable agreement that satisfies both sides; it is to define the limits of what Iran is allowed to become. The United States engages Iran in talks in order to codify constraints on its nuclear program, its regional influence, its technological development, and ultimately its capacity to act as an autonomous strategic actor. These negotiations are conducted under conditions shaped by overwhelming American military superiority. The military buildup in the region is not a contingency plan in case diplomacy fails; it is the condition that makes diplomacy possible on American terms. The threat of force is not external to the negotiation. It is embedded within it. Iran is invited to the table only after the boundaries of acceptable behavior have been predetermined by Washington and enforced through military pressure. The negotiation is therefore not a space of equal bargaining power but a mechanism through which asymmetry is reproduced.

Diplomacy as an instrument of strategic denial

Bolton’s comment reveals a deeper truth: the United States does not oppose Iran’s nuclear program solely because of proliferation concerns. It opposes it because a nuclear‑armed Iran—or even an Iran with a credible deterrent capability—would fundamentally alter the balance of power in the region.

A state with deterrence cannot be coerced in the same way. It cannot be forced to accept externally imposed limits on its sovereignty. It cannot be managed through periodic cycles of pressure and negotiation. The objective of U.S. policy is therefore not simply to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon. It is to prevent Iran from acquiring the kind of strategic independence that would allow it to resist American preferences. The negotiation is the diplomatic expression of this objective; the threat of force is its enforcement mechanism. When Bolton says “no decision is final,” he is not describing indecision. He is describing a deliberate strategy of uncertainty. By refusing to close off the possibility of a strike, the United States ensures that Iran cannot treat the negotiation as a stable framework. The instability is intentional. It keeps Iran reactive, cautious, and unable to plan beyond the immediate horizon.

The logic extends beyond Iran: the structural parallel with Ukraine

This pattern is not unique to U.S.–Iran relations. It is part of a broader architecture of American power. Ukraine offers a parallel example. For years, Ukraine was discouraged—both implicitly and explicitly—from developing the kind of military capacity that would have allowed it to deter Russian aggression independently. The result was a state that entered a major war without the means to defend itself and therefore became dependent on external support. A state that lacks deterrence lacks autonomy. It cannot negotiate from a position of strength. It cannot define its own security environment. It becomes subject to the strategic calculations of others. Today, Ukraine finds itself pressured to consider territorial concessions not because it desires them, but because its structural position leaves it with limited alternatives. Europe, too, is implicated in this architecture. After decades of aligning its security posture with Washington, it now confronts the consequences of its own lack of independent deterrence. It cannot shape the negotiations, it cannot guarantee Ukraine’s security, and it cannot act without American approval. The absence of deterrence produces not peace, but dependency.

The structural core is clear: states without deterrence are not negotiating—they are being negotiated.

From Tehran to Kyiv, the same logic governs the interaction between power and diplomacy.