The recent hearing before the U.S. House Judiciary Committee made the structural failures surrounding the handling of the Epstein files more visible than any previous disclosure. Lawmakers from both parties criticized Attorney General Pam Bondi for releasing only partially redacted documents despite a statutory obligation to provide broader transparency, and for missing the deadline for full publication. These are not mere procedural lapses; they reveal a deeper systemic problem.

New developments since the hearing reinforce this assessment. Several survivors publicly stated on February 12 that they still cannot find a single victim statement (302) in the released files. Survivor Jess Michaels described Bondi’s apology as “performative” and said the DOJ had “ignored and degraded” victims throughout the process.

This pattern aligns with the Department’s broader handling of the case, including its publication of millions of responsive pages and the release of the Epstein disclosures.

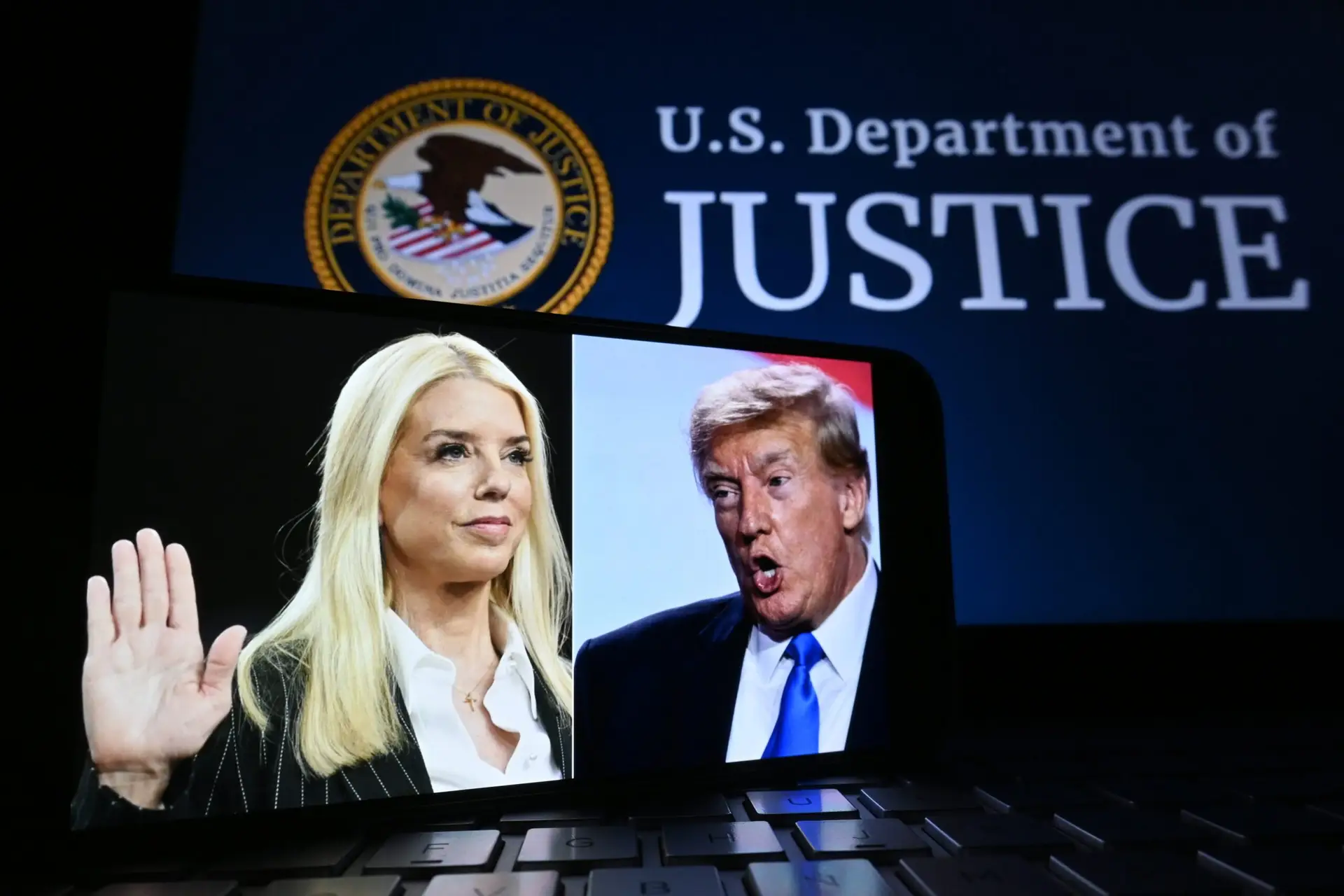

At the outset of the hearing, Democratic Representative Jamie Raskin positioned Bondi directly before the survivors seated behind her. He emphasized that justice is only possible when the voices of survivors are heard and when those responsible are named. Bondi offered a general apology for the victims’ suffering but refused to turn toward them when Representative Pramila Jayapal asked her to do so. Every survivor present raised a hand when Jayapal asked who had never been contacted by the Department of Justice—a moment captured [POLITICO2] repeatedly by survivors and observers. The scene exposed the profound distance between institutions and those they are meant to protect.

Republican lawmakers also voiced sharp criticism. Representative Thomas Massie questioned why the names of influential men were redacted despite legal requirements for broad disclosure. At the same time, intimate details about victims were released—an error Bondi acknowledged but dismissed as “unintentional.” The combination of excessive redactions, exposed victim data, and the missed deadline led several lawmakers to openly describe the situation as a “cover up.” On February 12, Republican members renewed this accusation publicly, arguing that the DOJ continues to shield powerful individuals while failing to protect victims.

When questioned by Republican Representative Chip Roy, Bondi stated that the Department of Justice was investigating “ongoing conspirators” connected to Epstein—a claim she later repeated without providing names or scope. It remained unclear whether she was referring to the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, which has examined Epstein’s ties to prominent individuals. Her vague remarks stood in stark contrast to the selective transparency of the released files. In subsequent public comments on February 12, Bondi escalated her rhetoric, attacking lawmakers personally rather than addressing the substance of the criticism.

The partisan dynamics underscored the depth of the structural issue. Republicans demanded closer scrutiny of Bill Clinton, citing his documented association with Epstein. Democrats pressed for a more thorough examination of Donald Trump’s long‑standing relationship with Epstein—tensions also reflected in the broader political discourse [POLITICO1]. Both sides used the case politically—yet both also demanded greater transparency. Since neither Clinton nor Trump has been accused of wrongdoing in this context, the bipartisan criticism reveals that the problem is not partisan. It is structural.

No U.S. law requires victim information to be exposed while potential perpetrators’ identities remain concealed. The selective transparency of the Epstein files is therefore not a legal necessity but the result of institutional choices. When victims’ data are made public while the names of powerful men remain hidden, a dual system of justice emerges: visibility for the vulnerable, invisibility for the influential.

The DOJ’s missed deadline, the ambiguous references to “ongoing investigations,” the selective redactions, the absence of meaningful engagement with survivors, and the increasingly defensive posture of the Attorney General form a coherent pattern: institutions protect themselves by controlling the visibility of power. Transparency is not applied according to principle but according to status.

The Epstein case illustrates why records must be visible, why procedures must be transparent, and why equality before the law is essential for institutional legitimacy. A justice system can only inspire trust when all individuals—regardless of influence, wealth, or political proximity—are subject to the same degree of scrutiny.

Power Lens:

This case demonstrates why transparency and equality of accountability are indispensable for restoring trust in institutions.

For more in‑depth reporting on politics, visit our Politics section.