When Ukraine is pressured by the United States to cede territory because Russia demands the full withdrawal of Ukrainian forces from the Donbas—including the 20 percent of Donetsk that Russia never managed to capture—this is not a peace negotiation but the preparation of a capitulation. The talks that began in Geneva on Tuesday and were officially intended to end the war concluded on the second day after less than two hours, when the Russian delegation left the venue. Both sides announced further rounds, but ending a war and creating peace are two entirely different things. Ukraine is being pushed to accept conditions it has rejected for the past four years. And this raises the question: Why did Ukraine fight for four years if it is now expected to surrender territory

Politically, the process is blocked because the central issues are irreconcilable. Zelenskyy himself said that there was progress on the military track but only “dialogue” on the political track—and that the positions remain far apart. These political issues are precisely the unresolvable points: the territories occupied by Russia, the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, the demand for territorial concessions, and the conditions of a ceasefire. Russia is demanding what Ukraine cannot accept under its own constitution, and the United States is pushing for a solution that undermines international law. This makes the political track not merely difficult—it makes it structurally blocked.

The reality is that political pressure on Ukraine does not end with the early conclusion of the Geneva round—it is structural, not situational. If territorial concessions are now being framed as “realistic,” it is not because circumstances have changed, but because international politics is willing to present a false solution as inevitable. Ukraine is militarily dependent on Europe and even more so on the United States. And before the war, it was not even permitted to build the military capacity it would have needed—Western states have consistently prevented countries outside the NATO framework from developing genuine defense autonomy, with Iran being the clearest example. The logic is absurd: a state that was not allowed to strengthen its defenses is now expected to surrender territory because it is not militarily strong enough. This is not the logic of peace but the logic of power. First self‑defense is restricted—and when war comes, the country is told to give up its land. Under international law, however, the prohibition on acquiring territory by force remains absolute, and the UN Charter makes clear that aggression cannot create lawful rights. Moreover, Article 52 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties holds that agreements concluded under the threat or use of force are void. In this sense, so‑called “realistic” territorial concessions made under political or military pressure cannot be regarded as sovereign decisions. What is presented as a peace process increasingly resembles an outcome shaped by structural coercion rather than genuine diplomacy.

Even after the early end of the Geneva session, U.S. political pressure on Ukraine continues: Ukraine is expected to accept conditions presented as a peace solution but which have nothing to do with peace. This is not a legal argument but a political one. A state without its own military deterrent cannot make free decisions. Under international law, agreements made under the threat or use of force are considered void, and territorial concessions made under political or military pressure cannot be regarded as free or sovereign decisions.

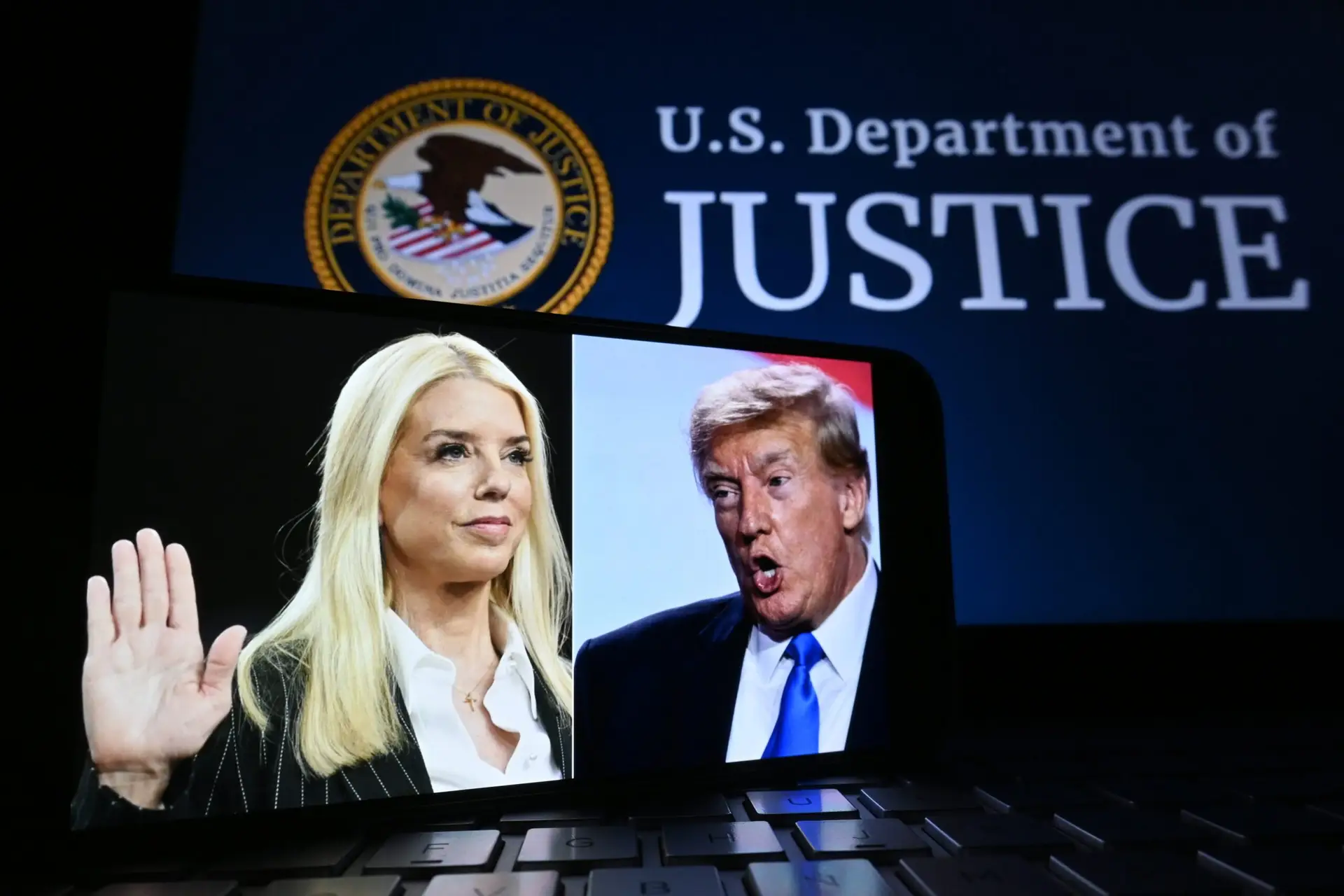

The American delegation in Geneva is unusually composed: Jared Kushner, Steve Witkoff, and U.S. Army Secretary Dan Driscoll. Parallel to the Ukraine talks, Witkoff and Kushner held indirect nuclear discussions with Iran in the morning—a rare attempt to manage two global crises simultaneously. Driscoll had already told European ambassadors that Europe could not match Russia’s arms production and that Ukraine was not militarily capable of recapturing lost territory. “Now is the best time for peace,” he said. It is the language of a power acting not out of moral conviction but strategic calculation.

The Ukrainian delegation is high-level: intelligence chief Kyrylo Budanov, Chief of the General Staff Andrii Hnatov, diplomats, military officials, and political representatives. Chief negotiator Rustem Umerov emphasized that the delegation was working “constructively, focused, and without excessive expectations.” The focus was on security guarantees, humanitarian issues, and an energy ceasefire. Yet while negotiations were taking place in Geneva, Russia continued attacking Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Just hours before the Geneva session, Russia carried out a large‑scale combined drone‑and‑missile strike across Ukraine. In Odesa, the impact was immediate: heating and water systems failed for tens of thousands, and several civilians—including children—were injured.

Europe was present in Geneva but without influence. Security advisers from Germany, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom were on site but spoke only on the margins with the Ukrainian and U.S. delegations. They did not participate in the actual negotiations. Mediation was entirely in American hands: Special Envoy Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner led the talks on Washington’s behalf.

The UN Charter is clear: Aggression is prohibited. Annexation is prohibited. Territory cannot be acquired by force. No state may compel another state to surrender land. But the Security Council is paralyzed—because of Russia’s veto. Russia is a veto state. The result: International law exists, but it is not enforced. A veto state can violate international law—and simultaneously prevent the international community from responding.

When the United States “decides” something, it does not change international law—but it changes reality. International law remains, but it is not enforced. International law exists because states agreed to it, codified it in treaties, and courts apply it—but it only becomes effective when power allows it.

Geneva does not show how peace is created. Geneva shows how peace is defined when power is unequally distributed. Ukraine is expected to accept what international law prohibits. Russia demands what it never conquered. The United States decides what is “realistic.” Europe watches. And the UN cannot enforce the law because a veto state blocks the very rules it breaks.

The result is a world order in which the aggressor may make demands and the victim is pressured into concessions. A world order in which military dependency replaces political decision‑making. A world order in which the language of peace is used to disguise the logic of power.

If a state that was not allowed to arm itself is expected to surrender territory in war, this is not a peace process but the retroactive legitimization of violence. And when international politics presents this as “inevitable,” it is not diplomacy but an admission that law without power is worthless.

Peace cannot emerge when injustice is declared the solution.

And as long as power overrides law, Geneva will not end this war—it will only reveal how unequal the world truly is.