When the United States pressures Iran to limit its nuclear program while simultaneously expanding its military presence in the region, this is not a negotiation between equals—it is an attempt to prevent a state from building the deterrence that would make it politically independent.

History shows that the absence of deterrence does not lead to peace, but to capitulation. Ukraine is dependent on the United States today because it was not permitted to build the military capacity it needed for its own security before the war. Now it is being pushed to surrender territory—precisely what Russia demands. Europe, after decades of political alignment with Washington, also finds itself without its own deterrent and unable to protect Ukraine or influence the negotiations.

The indirect talks in Geneva, held in parallel to the Ukraine discussions, ended without a breakthrough. Iran agreed to submit a written proposal addressing U.S. concerns, but the core issues remain unchanged: Iran will not abandon uranium enrichment, will not dismantle its missile program, and will not accept any arrangement that leaves the country strategically exposed.

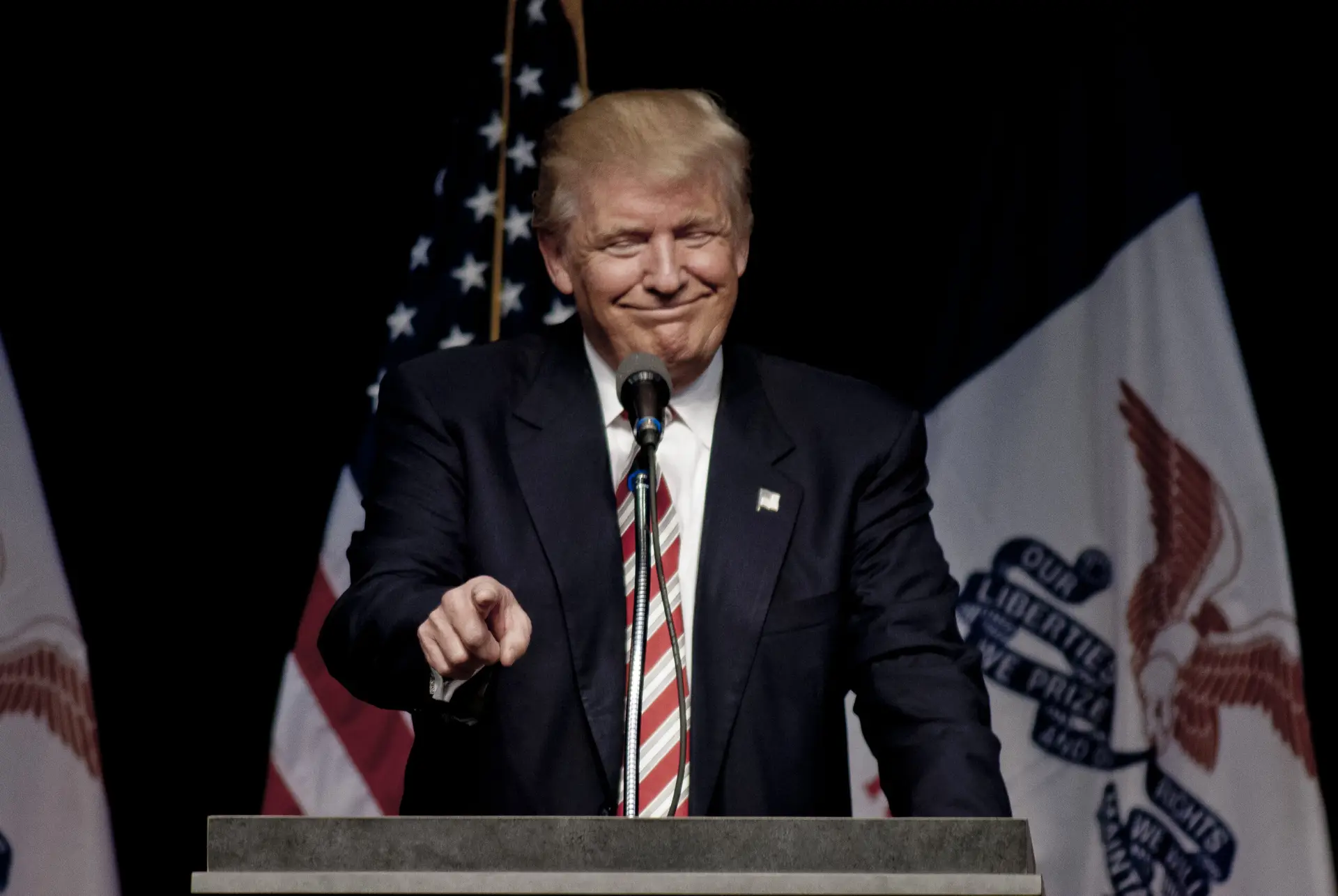

The United States, for its part, has deployed a second carrier strike group to the region, accelerated troop movements, and repeatedly signaled that military options remain on the table. President Trump has stated multiple times that a strike on Iran is possible if diplomacy fails. The message is unmistakable: these talks are taking place under the shadow of force.

Politically, the process is blocked because the central issues are structurally irreconcilable. Iran seeks security through deterrence; the United States seeks security by preventing Iran from obtaining it. These are not positions that can be bridged through dialogue alone. They reflect two opposing conceptions of sovereignty: one rooted in self‑defense, the other in containment.

The contradiction becomes even clearer when placed alongside the Ukraine case. Ukraine is being pushed toward concessions precisely because it lacks military deterrence. Iran refuses concessions precisely because it possesses it. A state without deterrence becomes dependent; a state with deterrence becomes uncooperative. This is the logic of power, not the logic of peace.

The United States argues that Iran must limit its nuclear program to prevent regional escalation. Iran argues that a state without deterrence shares the fate of those countries that were prevented from building defensive capabilities and later forced into territorial or political concessions. The comparison is politically sensitive but analytically unavoidable: a state that relinquishes its defensive capacity becomes vulnerable to coercion. Iran’s refusal to dismantle its deterrence is therefore not ideological—it is structural.

This dynamic was visible in Geneva. While U.S. envoys Jared Kushner and Steve Witkoff held indirect nuclear discussions with Iran in the morning, the same delegation spent the afternoon pressuring Ukraine to accept territorial concessions. Two crises, one logic: power defines the boundaries of what can be negotiated. States without deterrence negotiate under pressure; states with deterrence negotiate on their own terms.

Iran demonstrated this logic openly. Hours before the Geneva session, Iran conducted live‑fire drills and temporarily closed the Strait of Hormuz—a signal that it has the capacity to impose costs. The message was clear: Iran is not Ukraine. It cannot be forced into concessions through diplomatic pressure alone.

Regional actors—Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar, and Turkey—attempted to mediate, but Europe remained largely irrelevant. As in the Ukraine talks, Europe was present but without influence. The decisive exchanges occurred between Washington and Tehran, not in multilateral formats. The United Nations, constrained by geopolitical divisions, played no meaningful role.

International law provides a framework but does not resolve the core dilemma. The Nuclear Non‑Proliferation Treaty restricts nuclear weapons but does not prohibit states from seeking security. The UN Charter prohibits aggression but does not prevent great powers from using military threats as leverage. As long as enforcement depends on power, law remains secondary to strategy.

The Geneva talks with Iran, therefore, reveal the same structural truth as the Ukraine negotiations: diplomacy is not a neutral process. It is shaped by asymmetries of power, by the presence or absence of deterrence, and by the strategic interests of those states that define what counts as “realistic.

When a state that maintains its deterrence is pressured to dismantle it, while a state without deterrence is pressured to surrender territory, the message to the world is unmistakable: power determines sovereignty. And when international politics presents this as “inevitable,” it is not diplomacy but the normalization of coercion.

Peace cannot emerge in a system that punishes weakness and fears strength.

And as long as power overrides law, Geneva will not resolve the Iran crisis—it will only reveal how unequal the world order truly is.