The Four Lies of the World Order

The Equality of States—A Political Illusion

Iran’s centrifuges spin not out of ambition but out of fear. This fear grows from decades of isolation and sanctions and from the memory of governments that collapsed when they had no protection. The world sees uranium. Iran sees survival. And this difference in perception lies at the center of the Iran nuclear program and the wider struggle over Middle East security.

A History Written in Betrayal and Intervention

Iran’s fear did not begin with centrifuges. It began in 1953, when the United States and Britain overthrew Iran’s democratically elected prime minister. That moment left a wound that never healed, because it taught Iran that foreign powers could remove its leaders whenever they wished. And when the Shah fell in 1979, Iran entered a new era of isolation.

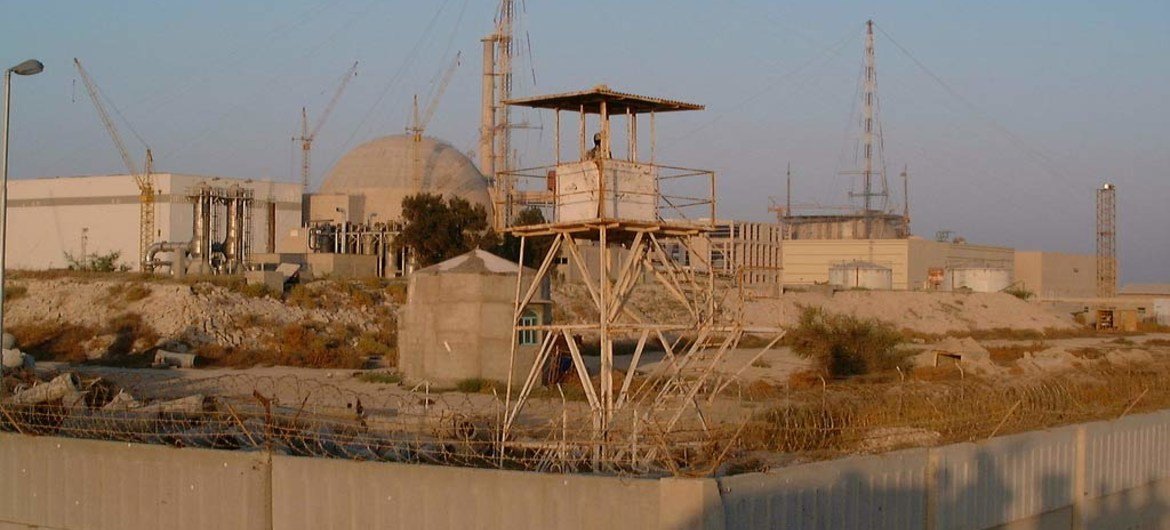

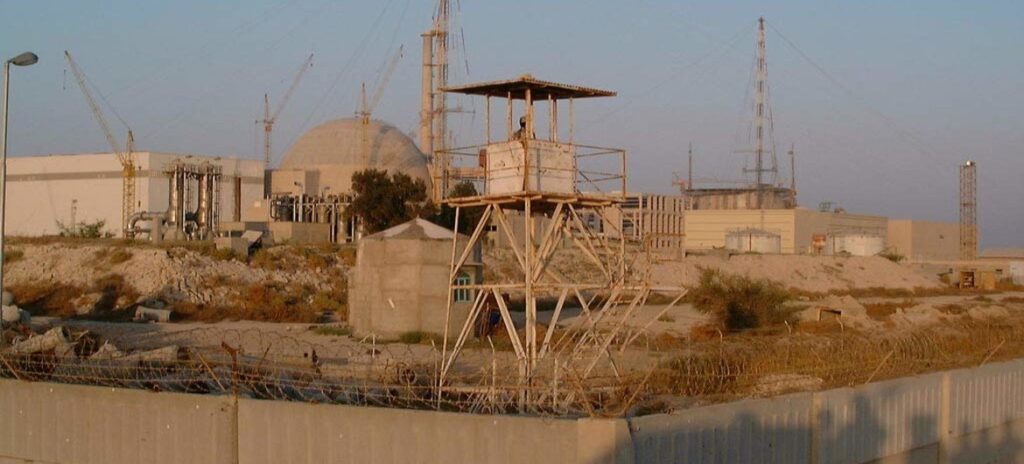

The Iran nuclear program itself began long before the Islamic Republic. In the 1970s, the United States, Germany, and France helped the Shah build a civilian nuclear energy sector. Iran wanted electricity and scientific progress, and the West wanted a stable partner. These origins matter, because they show that the Iran nuclear program was born as a modernization project, not as a weapon.

Everything changed after the revolution. Iran lost its allies and soon faced a brutal eight‑year war with Iraq. Saddam Hussein invaded Iran with the support of Western governments, and he used chemical weapons while the world looked away. Iran learned that no one would defend it. No treaties. No alliances. And no guarantees. Only self‑reliance. This history shapes Iran’s worldview far more than ideology ever could.

A Region Built on Imbalance

Iran lives in a region where power is unevenly distributed. Israel possesses nuclear weapons. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates buy the most advanced American weapons. The United States maintains more than 40 military bases around Iran. And the Strait of Hormuz—Iran’s economic lifeline—remains under constant US surveillance.

Iran sees these realities not as abstractions but as threats. And when a state feels surrounded, it seeks protection. That protection often takes the form of deterrence.

Iran also watched what happened to other governments that lacked deterrence. Iraq had no nuclear program when it fell. Libya gave up its program and collapsed. Afghanistan relied on foreign protection and lost everything. North Korea kept its weapons and remains untouched. These examples form the backbone of Iran’s strategic thinking. Iran does not seek confrontation. It seeks to avoid the fate of those who trusted the world and paid the price.

The Moment Suspicion Became Policy

In 2002, the discovery of undeclared facilities in Natanz and Arak transformed the Iran nuclear program into a global concern. Western governments feared that Iran could use the same technology for weapons, while Iran insisted that it wanted energy and medical research. Both sides spoke past each other, and mistrust replaced dialogue.

Uranium enrichment is not illegal. Many countries enrich uranium for civilian use. The problem begins when trust disappears. And trust disappeared long before Iran reached 60 percent enrichment.

The Rise and Collapse of Diplomacy

In 2015, the nuclear deal created a rare moment of hope. Iran accepted strict limits and inspections and reduced enrichment to 3.67 percent. In return, sanctions eased. The deal worked. Middle East security improved. And the world saw a path toward global disarmament.

Then the United States withdrew from the agreement in 2018. Iran lost the economic benefits and the political guarantees. And when a deal collapses, fear returns. Iran increased enrichment again and reached 20 percent and later 60 percent. This number sounds alarming, yet it remains a political signal rather than a military step. Iran wants to show that it can respond to pressure. It does not want a war that it cannot win.

Iran also continued to allow inspections for years after the US withdrawal, which shows that Iran did not rush toward a bomb. It waited for diplomacy. And diplomacy did not return.

Why 60 Percent Matters—and Why It Does Not Mean a Bomb

The jump from 60 percent enrichment to weapons‑grade material is technically short, although Iran still needs a political decision to take that step. And Iran understands that such a decision would bring disaster. A nuclear weapon would trigger regional escalation and international isolation. Iran wants the option, not the bomb.

Experts call this nuclear latency, which simply means the ability to build a weapon without choosing to do so. It is not a secret program. It is a warning to the world: “Do not attack us.”

Iran also lacks key components of a functional nuclear weapon: it has no tested warhead design, no miniaturized payload, no reliable long‑range delivery system, and no history of nuclear testing. A bomb is not a switch. It is a complex system that Iran has not built.

The Global Nuclear Order Rests on Inequality

The world focuses on Iran because it is easier than confronting the deeper issue. The global nuclear order rests on an old hypocrisy. Five states hold thousands of warheads and ask everyone else to trust them. They speak of stability while expanding their arsenals. They demand restraint while refusing to practice it. Iran reacts to this imbalance. It does not create it.

The Nuclear Non‑Proliferation Treaty obligates nuclear‑armed states to pursue disarmament. They have not done so. Instead, they modernize their arsenals and expand their military presence. Iran sees this behavior and concludes that the world rewards power, not compliance.

The UN Security Council reinforces this imbalance by allowing nuclear‑armed states to shape global rules while exempting themselves from them.

The Human Cost of Sanctions and Isolation

Sanctions have devastated Iran’s economy. They have weakened its currency, limited its access to medicine and pushed millions into poverty. These pressures do not weaken Iran’s resolve. They strengthen its belief that only deterrence can protect it from foreign coercion.

Iran has a young, educated population that wants stability and economic opportunity. Yet sanctions block investment, trade, and growth. A stable Iran would benefit the region. A cornered Iran becomes unpredictable.

Diplomacy Iran Tried—and the World Ignored

Iran has made several diplomatic offers that the world rarely remembers. In 2003, Iran proposed a Grand Bargain that included nuclear transparency, recognition of Israel’s borders, and cooperation against extremist groups, yet the United States rejected it.

In 2015, Iran accepted the most intrusive inspection regime in the world, and the United States later abandoned it. In 2021, Iran signaled willingness to return to the deal, but negotiations stalled. These moments show that Iran is not unwilling to negotiate. It is unwilling to surrender.

Why Disarmament Must Begin With the Great Powers

Real peace will not begin in Tehran. It will begin in Washington, Moscow, Beijing, Paris, and London. When the great powers reduce their nuclear arsenals, other states will no longer need nuclear shields. Middle East security will improve when the region stops living under the shadow of foreign intervention. And the Iran nuclear program will lose its purpose when Iran no longer fears collapse.

Global disarmament is not naïve. It is rational. It reduces the risk of war, lowers global tensions, and creates space for diplomacy. It also restores moral credibility to a system that has lost it.

A Different Vision of Security

Peace requires a new definition of power. Not power through weapons, but power through cooperation. Not dominance, but balance. Not fear, but trust. Iran enriches uranium because the world taught it that survival depends on strength. If the great powers choose global disarmament, they can teach a different lesson. And that lesson could finally break the cycle of fear.